|

CTM, Berlin’s world renown annual festival of ‘adventurous music and art’, is split in two this year. Part 1 occurred between 19 January and 6 February and featured exhibitions, concerts and an online discourse program. Part 2 proposes a return to the festival’s showcase clubbing events, 24–29 May. This year’s theme ‘Contact’, addresses the global COVID pandemic: ‘Few things have been made so ambiguous and unsettling by living with the virus as contact, encounter, and touch.’i

40 Years of Touch, Silent Green Kuppelhalle, 31/1.

The irony of London-based imprint Touch celebrating it’s 40th anniversary at CTM ‘Contact’ was not lost when it was announced that founders Jon Wozencroft and Mike Harding could not attend. Instead, Thomas Venker from Kaput magazine introduced the concert, recalling a recent conversation with the pair over Zoom.ii Venker relayed how from the beginning Wozencroft and Harding approached Touch as a lifetime project that was emphatically not a label, which would have a ‘long-term effect’—so they claimed not to be surprised about the anniversary and were looking forward to another forty years. Venker partially attributed Touch’s endurance to the founders ignoring marketing advice and instead finding their own rhythm and pace, which they also encouraged their artists to do. ‘You can’t hurry art’, says Wozencroft.iii

Indeed, Touch’s Berlin celebration rolled out unhurriedly. After delays at the doors of Silent Green’s Kuppelhalle, audiences hurried in from the chilly night to claim their seats in the domed octagonal-shaped auditorium of this former crematorium. Marta De Pascalis, replacing the Tapeworm before and in between performances, DJed a selection of music that spanned guitar drones, digitally stretched percussion, modulating synths and field recordings. Coupled with a slideshow of Wozencroft’s photographs, often seen on Touch releases, projected large above the stage, it set the context for the performances to come. The opening sets by crys cole and Oren Ambarchi, followed by Youmna Saba were my highlights. Also on the bill were Budhaditya Chattopadhyay and Ipek Gorgun.

40 Years of Touch, Silent Green Kuppelhalle, 31/1.

The irony of London-based imprint Touch celebrating it’s 40th anniversary at CTM ‘Contact’ was not lost when it was announced that founders Jon Wozencroft and Mike Harding could not attend. Instead, Thomas Venker from Kaput magazine introduced the concert, recalling a recent conversation with the pair over Zoom.ii Venker relayed how from the beginning Wozencroft and Harding approached Touch as a lifetime project that was emphatically not a label, which would have a ‘long-term effect’—so they claimed not to be surprised about the anniversary and were looking forward to another forty years. Venker partially attributed Touch’s endurance to the founders ignoring marketing advice and instead finding their own rhythm and pace, which they also encouraged their artists to do. ‘You can’t hurry art’, says Wozencroft.iii

Indeed, Touch’s Berlin celebration rolled out unhurriedly. After delays at the doors of Silent Green’s Kuppelhalle, audiences hurried in from the chilly night to claim their seats in the domed octagonal-shaped auditorium of this former crematorium. Marta De Pascalis, replacing the Tapeworm before and in between performances, DJed a selection of music that spanned guitar drones, digitally stretched percussion, modulating synths and field recordings. Coupled with a slideshow of Wozencroft’s photographs, often seen on Touch releases, projected large above the stage, it set the context for the performances to come. The opening sets by crys cole and Oren Ambarchi, followed by Youmna Saba were my highlights. Also on the bill were Budhaditya Chattopadhyay and Ipek Gorgun.

|

| 40 Years of Touch Oren Ambarchi & crys cole. Photo: Udo Siegfriedt/CTM 2022 |

Sitting

behind a table of electronics and assorted objects, Ambarchi cradled

an electric guitar while cole handled a mixing desk. As Ambarchi

teased out long dissipating guitar loops, cole seemed to work with

recordings, occasionally murmuring into a microphone. Their

performance seemed intuitive, like they were playing a game. When

Ambarchi adjusted his amplifier to fold layers of feedback into the

mix, cole inserted chirping birds. When cole blew into a wooden

flute, Ambarchi responded with a wooden whistle, their elongated

breaths weaving into each other. I sat delighted wondering where this

would lead, when they suddenly cut it off and they began the game

again with different sonic prompts.

|

| 40 Years of Touch Youmna Saba. Photo: Udo Siegfriedt/CTM 2022 |

Noting how certain sounds registered on different parts of my body, I later recalled the ethnomusicologist Steven Feld describing sound as touch, as air presses against our eardrums. He observes that sound is an ever-present sensation—we don’t have ear-lids! Both of these acts made use of stringed instruments vibrating in a room, amplification, processed sounds and voice, to produce surprising sonic aesthetics and (psycho)acoustic sensations. Their performances were confident, novel and unpredictable, commanding attention. Qualities that are surely lost over livestream.

Modular Organ System, Silent Green Betonhalle, 19–29/1

Philip Sollman and Konrad Sprenger’s performative installation was undoubtably the most expansive inclusion in CTM’s program. Sprawled across the large underground Betonhalle exhibition space at Silent Green, they showcased their deconstructed organ over several days of the festival.

Descending the long ramp into underground exhibition space was like crossing a metaphysical portal. Moving towards a white light at the end of the tunnel one came to a rack of speaker horns strapped to a trolley. Heaven is a thumping sound system, many would agree, and indeed Saint Peter was a security guard controlling the flow of punters during Covid restrictions.

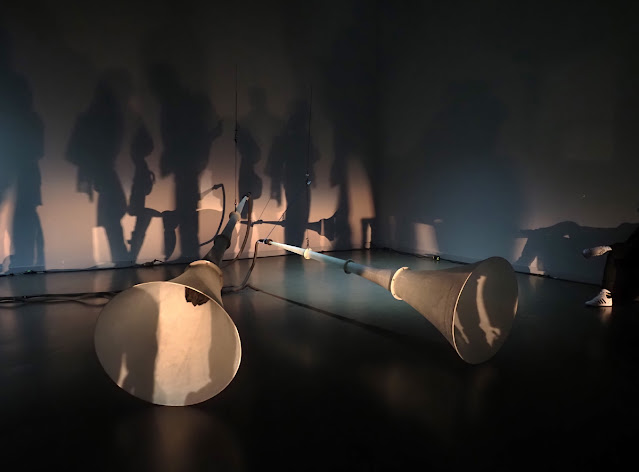

Down a flight of stairs into the sunken Betonhalle, one encountered a long conical horn, propped up on A-frames, running the length of the corridor — I’d guess 15 metres long — and pointing into the exhibition space. Here many other odd shaped speaker cones, pipes and horns were arranged, made from materials including fibreglass, paper mache and metals. Many of the objects were connected via tubes to wooden boxes housing air compressors, while others appeared to be stand-alone sculptures. The room-sized apparatus had a DIY feel, comprising materials that might have been sourced from Bauhaus. The centrepiece was a rotating arrangement of five horns and interlocking tubes that reminded me of the ad hoc plumbing in my share house. On opening night, spotlights beamed across the room into the mouths of horns and searchlights projected dramatic shadows on the bare walls. The room was buzzing and turning, seemingly automated by a pre-programmed score. ‘All stops out’, I punched into my notepad. Visitors wandered around inspecting details, occasionally pausing when stumbling into a sweet spot in the room. Some sat meditating before speaker cones.

|

| Phillip Sollmann & Konrad Sprenger - Modular Organ System. Photo: Udo Siegfriedt / CTM 202 |

The Stockholm-based composer Ellen Arkbro (20.1) is known for her subtle, minimal compositions. In a puffy black parka, she was a restless shadow fiddling with air compressors to release tone sweeps that invited sympathetic resonances. As speaker cones rattled around the space, I could hear the distinct materiality of resin cones and steel pipes. To me Arkbro seemed to be testing and tuning the instrument, ie the room, rather than performing a piece. In an interview she explains: ‘Listening to time passing is an aesthetic experience for me, it is the stage for the music.’v

Arnold Dreyblatt was the next guest (22.01). The media artist, composer and member of Berlin’s Akademie der Künste describes Sprenger (AKA Jörg Hiller) as his ‘most important collaborator’. Dreyblatt had installed numerous electric guitars on white plinths around the room. Attached to the instruments were motor-driven devices and magnifying glasses, inviting audiences to inspect how they had been treated. Some had their strings raised above the fretboards, enabling harmonics to ring out when struck at rapid speed — maximal microtones. Variation was most pronounced in the higher frequencies with the organ providing a stabilizing drone.

Dreyblatt and Sprenger occupied a taped off area where they presided over laptops and other gear, suggesting some signal processing. I listened for overtones as bass notes bubbled up. When I left Dreyblatt was bowing an electric double bass, one of his signature gestures.

Entering the following day for Brass Abacus (23.1), I found a quiet and attentive audience. A tuba player sat in the rotating horn sculpture emitting a static-like noise. Two trombonists were positioned at right angles in the room with the bulk of the audience gathered between. The musicians’ breathing was juxtaposed with the air powered organ setting a subtle background tone. After long sustained notes, the players’ occasional gasps and groans brought some drama to their focused performances. Brass sounds sharper and brighter than the System’s fibre glass cones, adding a distinct colour to the sonic spectrum. The beatings that occurred as frequencies approached each other registered as shifts in air pressure, with the piece gradually morphing from rasps and hisses into rich enveloping chords.

When I entered for Will Guthrie (28.1), he was positioned in the centre of the room with a drum set and a large hanging gong. He began to play, fidgeting and restless against a foghorn two note fugue puncturing the organ drones with dramatic shifts in volume and texture. A dynamic performer, Guthrie became the focus of attention and many in the audience intuitively tapped and nodded along. I observed someone dancing with small gestures and I found it odd how the rest of us suppressed this urge, inhibiting our capacity for ‘corpoliteracy’ — a critical lens invented by curator Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung.vi Guthrie and the System made the atmosphere thick, so when they stopped playing the silence was stunning. The pause between sets became an extended moment of anticipation — a cliffhanger.

|

| Kali Malone & Stephen O'Malley. Photo: Stefanie/CTM 2022 |

Kali Malone and Stephen O’Malley (30.1) performed together for the finale. O’Malley, known for his band Sunn o))), is doom-drone royalty. Malone’s recent album ‘The Sacrificial Code’ (2019) is a slow and revelatory composition for pipe organ. Their concert was sold out with a queue to enter.

Malone was set up on a table in front of what looked like an upright pipe organ. She sat focused over a box of knobs and a laptop on which I caught a glimpse of a symmetrically arranged Max patch. O’Malley occupied the opposite side of the room, against a barricade of well worn guitar amplifiers. As he applied an EBow to his guitar strings gear nerds ogled at his array of pedals, while others in the audience lay on the ground, absorbing the low rumbles into their bodies. My notes read: harmonics + air pressure = full frequency body massage. Malone filled the room with long notes that would suddenly shift, accentuating overtones. I listened for microtonal beatings, and moved around the room trying to hear heterodynes, before she ended abruptly. Long minutes passed before O’Malley eased air into a low frequency horn and struck a slow a metal riff on his thin transparent-bodied instrument; dissonant notes resolving into a major bar chord. I thought of the lowest known note in the universe, a B-flat, as O’Malley hammered his strings to sound a metallic klang that contrast the drone.vii

Fronte Vacou, Humane Methods [ΣXHALE], radialsystem, 6/2.

The final event of CTM Part 1 was a performance/installation, Humane Methods [ΣXHALE] from Fronte Vacou (vaccinated front), a ‘bastard performing arts triumvirate’ founded by Marco Donnarumma, Margherita Pevere, and Andrea Familari. Installed at radialsystem, a riverside theatre complex, Humane Methods [ΣXHALE] is described in the festival program as ‘a living biome’ in which the audience is ‘immersed’ into a garden-like habitat of human performers, plant and fungal life, and an omnipresent AI named <dmb>.viii

The final event of CTM Part 1 was a performance/installation, Humane Methods [ΣXHALE] from Fronte Vacou (vaccinated front), a ‘bastard performing arts triumvirate’ founded by Marco Donnarumma, Margherita Pevere, and Andrea Familari. Installed at radialsystem, a riverside theatre complex, Humane Methods [ΣXHALE] is described in the festival program as ‘a living biome’ in which the audience is ‘immersed’ into a garden-like habitat of human performers, plant and fungal life, and an omnipresent AI named <dmb>.viii

|

| Humane Methods [ΣXHALE] – Episode 1. Photo: Stefanie Kulisch/ CTM 2022 |

My ticket was for ‘Kategorie A’ and I shuffled into the designated door past a row of shambolic structures. Resembling greenhouses, they appeared to be made from scavenged materials; odd shaped plastic sheets affixed to wooden frames. I was ushered into one at the far end of the theatre. Inside, seats were arranged in rows for singles and couples with an aisle down the centre. There was a taped-off section behind us, presumably ‘Kategorie B’ in the tiered seating. After we claimed our spots, an usher entered with a stack of freshly laundered floppy red hoods. Covering our heads and hanging over our shoulders, we marked ourselves as a distinct group. I thought of The Handmaid’s Tale but we looked like a Smurf Armageddon — the absurdity of the mise-èn-scene. Sitting in anticipation, captive in our shattered shelter, I wondered if Kategorie B had the better seats, with a superior overview of the unfolding action.

After the doors to our greenhouse was shut and the lights dimmed, near naked figures appeared outside. They looked weary and distressed, as they pressed up against the flimsy barriers between us. They leaned onto each other and lurched around the perimeters of the structures and the thin alleyways between the three shelters. The performers closest to me dragged a thin and seemingly unconscious man with distinctive full body tattoos. They made eye contact and caressed the walls, provoking empathy when they massaged the thin man’s legs. Another performer attempted to scale the walls of an adjacent structure. He failed to establish a grip and slid back.

I looked for hand signals and the performer closest to me made a gesture reminiscent of a cross. Small flat screens installed at head height flickered on: ‘Found Pattern 881.0’. I noticed one of the performers held a camera wrapped in a dirty rag, but the image on screen was not anything I could distinguish; high contrast and blurry; ‘Loop corrupted’. The soundtrack segued into what sounded like suspenseful strings and a stool was knocked over. The lights flickered off briefly and I sensed the action was reset, as performers raced back then again staggered down the aisle to tend to the unconscious man.

As a meditation on ‘algorithmic violence’ where action and automation are integrated and repetition implied a cathartic ritual, Fronte Vacou presented an obtuse allegory.ix After an hour or so, the house lights faded up and the glasshouse doors were opened, which we took as a cue to leave. The performers continued in the aisles as the theatre emptied. No explanation, resolution or relief; a dystopian garden of no respite.

|

| Humane Methods [ΣXHALE] – Episode 1. Photo: Stefanie Kulisch/ CTM 2022 |

According to CTM:

The pandemic has rendered many things we once took for granted fragile. Among them is the certainty that music holds spaces for us, where freedom, closeness, exuberance, and community are within reach … the inequality-reinforcing effect of the pandemic becomes apparent, because reducing contact might not be something one can afford, and its ramifications depend directly on their respective social status and economic resources.x

I have no doubts about the significance of CTM to contemporary music and club culture so I certainly felt privileged to attend Part 1 physically, when so many — including those in the program — could not. Following threads on CTM’s Discord and Telegram channels, it occurred to me that electronic music communities might have more easily adapted to pandemic conditions, as much music production, distribution and promotion occurs via file sharing over networks, even while being together in sound is sorely missed. ‘Contact’ could also mean interpersonal networks that are ‘technologies of care’ — as Daphne Dragona, former Transmediale curator, might say.xi So while ‘music holds space for us’, CTM proves it is also an infrastructure for care, having established a context from which diverse organizing interests can begin.

–

i “CTM 2022 Festival Theme”ii See Thomas Venker’s interview with Jon Wozencroft and Mike Harding, “TOUCH: ‘We survived because there’s a lot of things that we chose not to do, which has worked out really well’ ”, Kaput, 22 February 2022.

iii See Mike Harding interview by Bana Haffar, Brussels, May 4th, 2019.

iv See ‘Youmna Saba’ (interview), Cité Internationale des Artes, n.d.

v “Fifteen Questions Interview with Ellen Arkbro: A Tender Moment”, Fifteen Questions, n.d.

vi Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, “Corpoliteracy”, In S. Angiama, C. Butcher, & A. Zeqo (eds.), aneducation, documenta 14, Archive Books, Berlin, pp. 107–115.

vii “Interpreting the ‘Song’ Of a Distant Black Hole”, Goddard Space Flight Centre, 17 November 2003.

viii “Humane Methods [ΣXHALE] – Episode 4”.

ix See “Fronte Vacou ΣXHALE”

x “CTM 2022 Festival Theme”

xi Daphne Dragona “Technologies of care: networks, practices, infrastructures”, 12 December 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment